|

Contents

Overview - Iraq's Children: A Lost Generation. . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

South and Central Iraq . . . . . . . . . . 9

Northern Iraq. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Unicef in Iraq . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

South and Central Iraq. . . . . . . . 17

Northern Iraq . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

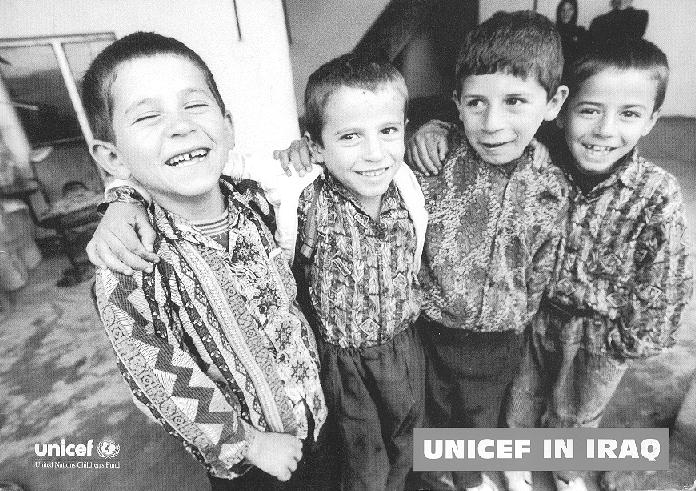

Text by Tamara Sutila

Photography & Design by Giacomo Pirozzi

DTP by Caroldean Lamprecht

Repro and Printing by Business Print Centre, Pretoria, South Africa

May 2001

Overview

Iraq's Children: A Lost GenerationAt the end of the 1970s, Iraq was a powerful and respected state, just beginning to emerge as a regional power and booming on petrodollars from some of the world's largest oil reserves. Two decades later the situation has drastically changed due to two devastating wars and the effects of international sanctions.

The United Nations Security Council imposed economic sanctions on Iraq on 2 August 1990. Under the sanctions, all imports to and exports from the country were prohibited unless the Security Council gave its go-ahead. These sanctions have proved to be the toughest, most comprehensive sanctions in history.

Mounting evidence shows that the sanctions are having a devastating humanitarian impact on Iraq. Since 1990 there has been a severe and prolonged deterioration in the standards of living of the vast majority of Iraqis. The country has experienced a shift from relative affluence to massive poverty. In 1997, the United Nations Human Rights Committee noted that "the effect of sanctions and blockades has been to cause suffering and death in Iraq, especially to children". UNICEF's Executive Director, Carol Bellamy, stated that if the substantial reduction in child mortality throughout Iraq during the 1980s had continued in the 1990s, half a million fewer children under the age of five would have died during the eight year period from 1991 to 1998.

In December 1996, the United Nations and the Iraqi government agreed to an 'oil-for-food' programme which allowed Iraq to export oil and use part of the money raised to buy basic goods from other countries. Since Iraq is using its own money to buy goods, the programme is not considered 'humanitarian aid' but rather as a temporary measure to ease the impact of the sanctions. The programme is organised in six month 'phases'.

To date the oil-for-food programme has not had a positive impact on the Iraqi economy although it was never meant to act as an adequate substitute for the independent functioning of the economy. While 2000 saw more countries and companies establishing direct ties with Iraq, the national economy did not show signs of recovery as hyperinflation, unemployment and the depreciation of the national currency continued to rise unabated. In Northern Iraq, the economy continued to be completely dependent on informal trade with goods brought in from Turkey and Iran.

Humanitarian agencies have reported that while the humanitarian crisis in south and central Iraq continues, there has been a decline in infant and child mortality rates in the autonomous Northern Iraq. There are many factors that have contributed to this situation. The north has benefited from the heavy presence of aid agencies helping the Kurdish population. The north has also received 22 per cent more per capita from the oil-for-food programme and about 10 per cent of this assistance in cash while the rest of the country can only use these funds to import commodities. This means that in Northern Iraq, a cash component has been used to implement projects more effectively while in the south and centre, local authorities have received water pumps but have not had the money to pay contractors to install them. It has also been difficult to enforce the sanctions rigorously in the north because of a more porous border than in the south and centre.

The specifics of the original oil-for-food programme have been changed in subsequent Security Council resolutions. In December 1999, Security Council Resolution (SCR) 1284 removed a cap on oil sales by Iraq, created 'green lists' of supplies which could be imported without individual approval by the UN sanctions committee and allowed a cash component to pay for local costs of implementing the programme.

A cash component is considered essential to improving the effectiveness of the oil-for-food programme in the south and centre of Iraq. UNICEF has been strongly advocating for this since the introduction of the programme. With increased funding levels and volume of supplies being delivered to Iraq, a cash component can significantly improve the effectiveness of programme implementation and therefore improve the welfare of children and women in the country. While a "cash component" to the oil-for-food programme has been provided for in several Security Council Resolutions there is still no agreement on how this could be implemented.

The oil-for-food programme has largely stopped the humanitarian crisis from worsening, especially as it has helped to provide improved food rations for ordinary Iraqis. The programme however has not been able to solve the severe humanitarian problems. It needs to be supplemented by massive investments in key sectors, including oil, energy, agriculture and sanitation. Clean water and reliable electricity, for example, are of paramount importance to the welfare of Iraqi people. Although food rations delivered by the government are in principle covering the caloric intake of the population, people have become so poor that in some cases, they are selling their rations to buy other essential goods.

One of the limitations of the oil-for-food programme is the increasing number of holds placed on imports to Iraq by the UN sanctions committee, especially in the south and centre of the country. Current holds on such sectors as electricity, water and sanitation and agriculture keep essential supplies from being delivered in time and adversely affect the impact of the programme.

South and Central Iraq

The cumulative effects of the two wars and the sanctions have taken their toll on the Iraqi population in the south and centre of the country. This region is home of 85 per cent of the country's population. The delivery of social services for women and children has greatly deteriorated. The emotional and psychological stress on children and women living with war and deprivation has been high. The WHO pointed out that the number of mental health patients visiting health facilities rose by 157 per cent from 1990 to 1998. The social cohesion of Iraqi society has become fragile, seen by rising juvenile delinquency, begging, criminality and cultural and scientific impoverishment. A whole generation of Iraqis is growing up disconnected from the rest of the world.

Infant and Child Mortality surveys conducted by UNICEF in 1999 revealed that children under the age of five were dying at more than twice the rate they were ten years ago. The current rate of 131 deaths per 1000 live births is comparable to that of Haiti or Pakistan. The health care system is in a decrepit state and there has been a massive deterioration in water supply and waste-disposal systems. Since 1991, hospitals and health centres have gone without maintenance. The functional capacity of the health care system has degraded further by shortages of water and power supply, lack of transportation and the collapse of the telecommunications system. Communicable diseases such as water borne illnesses and malaria, previously under control, came back in epidemic portions in 1993. Diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections account for 70 per cent of all child deaths.

Although the oil-for-food programme ensures a certain level of food security for Iraqi families, it has not improved the quality of consumed food. Malnutrition rates remain high, especially for children. An assessment by the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) in 2000 found that 10 per cent of children under the age of five had acute malnutrition when in 1991 the rate was at 3 per cent. One in five children remain so malnourished that they need special therapeutic feeding. Child malnutrition is caused by factors other than those related to food, notably disease and unsafe water. Overcrowding, poverty and the lack of education are also contributing elements. UNICEF nutrition surveys carried out over the past four years show that since the introduction of the oil-for-food programme, the nutritional status of children has stabilised---but it has not improved significantly.

Immunisation coverage on the other hand, has improved. Tuberculosis coverage rose dramatically during 2000 to 99 per cent compared to 85 per cent the previous year. Sixty per cent of pregnant women received their tetanus jab against 51 per cent in 1999. Coverage rates for children under one year of age remained relatively high --- 87 per cent for polio 3, 87 per cent for diphtheria and 92 per cent for measles. Efforts to eradicate polio were intensified during 2000 with mass national polio immunisation campaigns. These helped bring the polio coverage to 97 per cent. The Ministry of Health reported only four cases of polio in 2000 compared to 77 cases the previous year. There have been no reported cases since January 2000.

The substantial progress made in reducing adult and female illiteracy has stopped and regressed to mid-1980 levels. More and more pupils and teachers are leaving the school system. More than half of all schools are unfit for teaching and learning because they need substantial repairs. The Ministry of Education has recently said that 23 per cent of children between the ages of 6 and 15 are now working in the street to supplement family incomes and that Iraq can no longer enforce its laws on compulsory education. Nearly all urban schools have two shifts of classes and the curriculum has not been revised for the last 20 years.

A drought in 1998-99 has greatly reduced the capacity of hydrostations to generate electricity. During the summer months power cuts last up to 18 hours a day, severely affecting water and sewage treatment plants, health centres and other vital social services. Poor water supplies and inadequate sanitation have contributed to frequent and repeated infections compounding child malnutrition. The drought has also decreased crop production and more food has to be imported under the oil-for-food programme.

This humanitarian crisis persists and the situation is made worse by the lack of progress in stopping the continuous decline in essential social infrastructure. It is hoped that with the implementation of a cash component for south and central Iraq, it will be possible to upgrade the infrastructure and improve managerial and technical skills of local professionals --- all essential steps to be taken to end this crisis.

Northern Iraq

From the mid 1970s to the mid 1980s, social services like health, basic education and water and sanitation were readily available, at least in all the urban centres of Northern Iraq. They were well managed and maintained, often by expatriate technical personnel. A reasonable portion of the country's oil wealth was invested in providing social services to all its citizens. There were also investments in agriculture and food production and not only was Northern Iraq self sufficient in food grains but also supplied the rest of the country.

The Iraq/Iran War in 1980 changed Northern Iraq for the worse. Northern Iraq's border with Iran became a critical battle front in this war. A series of political events over the next decade led to a virtual collapse of social services. The Iraq/Iran War, the Gulf War in 1990, and the ensuing sanctions choked off investment in essential social services. The armed conflict between the two leading Kurdish political parties in Northern Iraq led to further disruptions during 1994-97. Extensive use of mines along the Iraq-Iran border as well as within the three governorates led to further problems.

Children and women were the most severely effected during these years of disruption and armed conflict. The health status of the population declined from 1991 onwards. The mortality rate for children under five give rose from 80 deaths per 1000 live births in the period 1984 to 1994 to 90 deaths per 1000 live births for 1989 to 1994. This has since improved to 72 deaths per 1000 live births.

In addition to the damage caused to health centres during these conflicts, imports of essential medical supplies stopped and trained health personnel left the country. Similarly the fighting disrupted basic education and schools were not only closed, but many were also destroyed. Working children and orphan children emerged as a social phenomenon in the mid 1980s and continued to increase as many families lost breadwinners in the wars or due to internal displacement and the deteriorating economy. A special problem of internally displaced persons emerged in Northern Iraq as entire villages were resettled. Water and sanitation systems in the urban centres broke down because of lack of maintenance.

Since 1997 and the beginning of the oil-for-food programme, the situation has gradually improved, although in a very uneven manner. The UN has allowed the import of essential supplies for all social services. Free food rations have ensured that basic food needs are met for all the population. Chronic malnutrition in children has been declining. Intensive efforts by UN agencies, NGOs and the other international donors have made the population healthier through immunisation and disease control campaigns and restoration of clean drinking water supply. By early 2000, the total quantity of drinking water available increased to 20 per cent over the 1990 level. Schools, primary health care centres and drinking water supply systems have been rehabilitated. More than 90 per cent of children attend primary school. However more boys than girls are sent to school, reflecting the prolonged negative impact of the sanctions on families and the lack of awareness of the importance of girls' education.

Even though infrastructure and supplies have been restored, services to remoter rural areas are still a neglected issue and the urban-rural divide in Northern Iraq has widened. Local authorities are not experienced in working sensitively with orphans, children with psychological trauma and mine victims.

With the large exodus of trained personnel, all services are undermanaged and face an acute shortage of technically trained personnel. Free food rations, combined with the drought in 1998-99, have led to a sharp fall in food prices, but at the expense of local food production. The oil-for-food programme's short, six month resource allocation cycles mitigate against any long term planning. This has created greater dependency on the programme at the expense of sustainability and local self reliance.

UNICEF in Iraq

UNICEF has been working in Iraq since 1983 to help the government promote the survival, protection and development of children. UNICEF has programmes in the areas of water and sanitation, primary education, health and nutrition and children in need of special protection.

The UN in Iraq gets 98 per cent of its funding from the Security Council Resolutions which make up the nine phases of the oil-for-food programme. UNICEF is the only UN agency that maintains a sizable regular country programme in Iraq. Since the introduction of oil-for-food in 1996, UNICEF has been able to ensure that the situation and needs of children and women are critical measures of the success of the programme.

South and Central Iraq

UNICEF's current programme of cooperation with the Iraqi government has two main roles:

1. To help assess the situation of children in Iraq, track changes over time and advocate for more to be done to help children.

2. To use UNICEF's resources to supplement the oil-for-food programme by providing cash for skills training, capacity building, rehabilitation and distribution of supplies.

Nutrition

The Targeted Nutrition Programme is centred around Community Child Care Units. Run by local volunteers, the Community Child Care Units screen children under five years of age for malnutrition. High protein biscuits and therapeutic milk---made available through the oil-for-food programme---are also distributed to severely and moderately malnourished children and to pregnant and lactating mothers. More than 2500 units have been established throughout south and centre of the country --- about 85 per cent of the target number. During the first three months of 2000 more than 1.5 million under five year old children were screened for malnutrition and these children's caretakers were provided with nutrition education. UNICEF also ran intensive mass mobilisation campaigns to ensure that high protein biscuits were used properly by families as supplementary food for malnourished children.

Health

UNICEF has also been supporting efforts to eradicate polio from Iraq. In 2000 two rounds of Polio National Immunisation Days reached 97 per cent of children. In addition, a Supplementary National Immunisation Day was held and covered 70 per cent of Iraq. The Ministry of Health confirmed only 4 polio cases in 2000---all during January 2000---compared to 77 cases in 1999. The success of these efforts are based on high political commitment, extensive social mobilisation campaigns combined with active participation from communities. UNICEF also supports routine immunisation activities called the Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI).

Primary Education

UNICEF has continued to support the physical rehabilitation and reconstruction of primary schools in four governorates. In 2000 a further 55 schools were rehabilitated in Baghdad, Missan, Basra and Thiqar. This has brought the total number of rehabilitated schools over the past two years to some 325, benefiting over 35,000 students and 1600 teachers. This project has benefited from substantial funding from the European Community Humanitarian Organisation (ECHO) during 2000.

UNICEF also strives to improve the quality of teaching in primary schools. More than 400 school supervisors have been trained as trainers and 554 teachers were trained in teaching English, maths, health, ecology, special education and in teaching large classes.

Child Protection

In collaboration with the NGO, Enfants du Monde, UNICEF is helping strengthen the skills of professionals working with street children through specialist training and study visits to other countries. UNICEF is also supporting a community-based programme for detecting and helping children with disabilities. Officials involved in this project were sent on a study tour to Jordan where they visited successful community projects for children with disabilities. UNICEF and Enfants du Monde have set up libraries in more than 60 schools and children's homes, benefiting around 3750 disabled children, orphans and street children. Each library has been provided with 270 books and more than 100 titles of books recorded on tape. UNICEF is supporting a TV series for the deaf to popularise sign language among parents and communities. Funds have also been provided to rehabilitate and equip two orphanages.

Water and Environmental Sanitation

UNICEF's strategy of complementing the inputs from the oil-for-food programme is most clearly seen in the water and sanitation sector where UNICEF provides complementary cash support for installation and utilisation of supplies. Through this strategy UNICEF has supported the rehabilitation of more than 40 water and sewerage treatment plants over the last three and a half years, improving services for more than 7 million people in the south and centre of Iraq. UNICEF has also helped train more than 80 operators and technicians during 2000.

Northern Iraq

In the three autonomous northern governorates of Iraq UNICEF is responsible for implementing and monitoring the oil-for-food programmes for water and sanitation, primary education, nutrition, primary health care and programmes for children in need of special protection.

Water and Sanitation

The water and sanitation programme focuses on securing universal access to safe water and sanitation and reducing differences in access between rural and urban areas. This is being done through the use of appropriate technology, training, provision of equipment and supplies, water quality monitoring and community participation. The programme also promotes hygiene education in schools.

In urban areas, UNICEF has helped install water pumps, provided generators and transformers to pumping stations and replaced or extended water distribution systems. This helped increase water availability from 110 litres per person in 1996 to 150 litres in 2000. Nearly 1.2 million people are benefiting from 496 pumps that have been installed in urban areas. The installation of more than 449 chlorinators and the provision of other water treatment chemicals has helped improve water quality. Some 1000 pump operators and engineers have been trained in pump operation and maintenance. UNICEF has also provided 171 sanitation vehicles to help dispose solid and liquid waste and has constructed 28 kilometres of sewage channels up to December 2000.

In rural areas, UNICEF, in cooperation with local authorities and NGOs, has built or rehabilitated more than 1200 rural water schemes, benefiting 378,000 people. This has raised access to water for rural people from 63 per cent in 1996 to 82 per cent in 1999. The number of villages that now have safe water has increased from 1,788 in 1996 to 2,599 in 2000. To make communities more self-relient, UNICEF supported training for 4,718 village operators in charge of managing village water pumps. These individuals also mobilise other community members to contribute fuel for the pumps and conduct minor repairs.

UNICEF runs a pilot project on school sanitation and hygiene education to improve hygiene practises amongst children, families and communities. Schools are used as a vehicle to promote hygiene messages. School toilets and water supply systems have been rehabilitated, mobile health teams visit the schools and conduct health check-ups and teachers give lessons in six different hygiene topics.

To help local authorities cope with the drought and diminishing water supplies, UNICEF sent 100 water tankers to 475 villages and 25 towns. New wells have also been drilled.

Health

The health programme addresses the main causes of death and illness among children and women, and strives to promote safe motherhood. It also focuses on immunisation against six child diseases, polio eradication; strengthening the primary health care and training in management of child diseases.

In 2000, routine immunisation activities took place despite shortages and often-erratic arrival of some vaccines. UNICEF supported National Polio Immunisation Days and provided 1.5 million polio doses. Mobile vaccination teams inoculated children in high-risk communities such as the nomads, displaced people and remote villagers. In 2000, 103 per cent of children under one year of age were immunised against tuberculosis, 74 per cent against diphtheria, 76 per cent against polio 3 and 92 per cent against measles.

To promote safe delivery techniques in remote areas, UNICEF held courses for 652 traditional birth attendants in rural villages. In addition, 164 health workers in antenatal clinics were trained in maternity care. Lack of female staff in remote health centres is a major constraint to this project.

To help control diarrhoeal diseases, one of the leading causes of child deaths, UNICEF gave support to 15 cholera watch teams. Health staff in clinics were trained in oral rehydration therapy. UNICEF provided health centres with 390,000 sachets of oral rehydration salts (ORS).

To increase access to primary health care, UNICEF helps rehabilitate health centres. More than 60 health centres were rehabilitated during 2000. Eleven mobile health teams also visited primary schools throughout the north, carrying out check-ups and teaching children and teachers about proper hygiene.

Nutrition

The nutrition programme aims to improve the nutritional status of children under five and pregnant and lactating mothers. Large-scale screening for malnutrition and targeted nutrition programmes are key parts of the programme, which also aims to reduce deficiencies in iodine and Vitamin A.

UNICEF focuses on early detection of child malnutrition by conducting regular nutrition surveys. Between 1994 and 2000, eight surveys have been carried out. These studies not only measure the prevalence of malnutrition but also help build the skills of local experts involved in the surveys and advocate for greater efforts in reducing malnutrition. Between 1994 and 1999, acute malnutrition has dropped from 4.2 per cent to 1.8 per cent. Similarly chronic malnutrition has decreased from 37.3 per cent to 18.3 per cent. UNICEF addressed malnutrition through growth monitoring units at the primary health care level. These units screen children and treat cases of malnutrition. There are now 360 such units which screen an average of 90,000 children a month.

UNICEF has also trained more than 4000 primary health workers in the use of growth monitoring equipment, breastfeeding promotion and prevention of vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Mobile monitoring teams are in the field to oversee the nutrition and preventative health care programme in primary health care centres. Television spots are aired to encourage breastfeeding. Mobile health teams travel around schools and villages, teaching communities how to prevent malnutrition.

Primary Education

The education programme's goal is to improve access to primary education by renovating schools, providing student kits and building local capacity to print text books in the north.

It is currently estimated that 90 per cent of children are enrolled in the first grade of primary school. While this is encouraging, gaps remain, particularly in remote rural areas. Since 1998, UNICEF has rehabilitated 384 primary schools, mostly in urban areas. Now, a new project has been set up to increase access to primary education in rural areas. With UNICEF support, the Ministry of Education and community members are building 298 schools in villages. This initiative will benefit approximately 7450 students. UNICEF has also provided more than 7000 desks to newly rebuilt schools. Around 690,000 children have received school stationary kits so that they have pencils and copy books to use for their learning.

UNICEF has been supporting teacher training since 1997. In 2000, nearly 1000 teachers were trained in maths, Kurdish, English, sciences and modern teaching methods. More than 3000 primary school teachers got training on mine awareness. UNICEF has also been strengthening the capacity of Ministry of Education staff to collect data on the current state of affairs in primary education and to plan for future programmes.

In 1999, 1.3 million text books were printed, an output fivefold greater than the annual average of 400,000 books during the 1991-97 period. However the quality of printing needs to be improved. UNICEF has supported this process by providing computer equipment and software for Kurdish fonts to the printing presses. Software training was also conducted for printing staff. UNICEF helped education authorities transport two million textbooks from Baghdad to the north.

Child Protection

The child protection programme seeks to improve the lives of disabled children and other children in need of special protection, by training health professionals and social workers, and supporting production of artificial limbs and aid items.

A pilot project is underway to detect childhood disabilities in three primary health care centres. Children are screened twice a week with 7800 children screened to date. Out of these 169 children were referred to specialists. UNICEF also provides essential supplies and raw material for the production of artificial limbs and aid items. UNICEF support through prosthetic centres reaches some 2000 disabled children per month.

In 2000 UNICEF supported the training of 120 doctors and social workers on psychosocial treatment for traumatised children. UNICEF is also supporting the development of a Kurdish sign language dictionary for deaf and mute people. The dictionary will be the first of its kind in the region.

According to a UNICEF assessment of street and institutionalised children in the north, the majority have contact with their families. It is therefore important to help these children return back to their families and UNICEF is designing a reintegration programme for this purpose. UNICEF also provided generators for vocational training centres attended by street children.

In 2000, a seminar on Juvenile Justice was held and proved to be useful in pointing out the weakness in this area in Northern Iraq and an entry point for further work. Activities to promote the Convention on the Rights of the Child included television programmes, a children's rally and a drawing exhibition.

UNICEF

United Nations Children's Fund

Hay Abu Nawas, Mahala 102,

Zukak 12, Building 4

Baghdad, Iraq

Fax: 873-761-473-376 & 873-761-351-893 (Satcom)

Telephone: 873-761-473-574/5 & 873-761-351-892 (Satcom)

National Telephone: +964-1 -719-2318/9 & +964-1-719-7921

e-mail: baghdad@unicef.org

[Scanned, OCR'd, and posted on web - AKF 7/14/2002.]