|

DONALD B. SCARAMASTRA, WSBA #21416 GARY D. SWEARINGEN, WSBA # 24483 GARVEY SCHUBERT BARER Attorneys for Plaintiff Bertram Sacks |

|

|

Court Use only above this

line. |

|

UNITED

STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON

AT SEATTLE

|

BERTRAM SACKS, Plaintiff, vs. OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY, Defendant. |

NO. COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE

RELIEF |

Plaintiff Bertram Sacks alleges:

I.

pARTIES

1. Plaintiff Bertram Sacks is a citizen of the State of Washington. He resides in Seattle, Washington, in the Western District of Washington. This case arises from Mr. Sacks’s journeys to Iraq. On each trip, Mr. Sacks has brought medicine and medical supplies for use in civilian hospitals there. He has done so to publicize and ameliorate the effect of economic sanctions imposed by the government of the United States. These sanctions have led to widespread suffering and death of Iraqi civilians, especially children.

2. Defendant Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) is an agency of the government of the United States government. In furtherance of, and as part of, economic sanctions, OFAC has promulgated regulations that prohibit certain transactions in Iraq. Purporting to act under those regulations. OFAC has announced its intention to impose a $10,000 civil penalty on Mr. Sacks for traveling to Iraq with medical supplies.

3. OFAC’s fine, and the regulations under which OFAC imposed that fine, violate statutory law, executive orders, international law, and the United States Constitution. Mr. Sacks seeks injunctive relief, and declaratory relief under 28 U.S.C. § 2201, that will stop OFAC’s unlawful enforcement of an alleged $10,000 civil penalty against Mr. Sacks.

II.

JURISDICTION AND VENUE

4. This Court has jurisdiction of the subject matter under 28

U.S.C. §1331, as this case arises under the laws of the United States. This Court also has subject matter

jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1337, as this case arises under an Act of

Congress regulating commerce. This Court

further has subject matter jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1346(a)(2), as

this is an action against the United States for an amount not exceeding $10,000

and founded upon the Constitution, Acts

of Congress, and regulations promulgated by the defendant. This Court further has subject matter of this

action, as it has jurisdiction of the underlying claims by OFAC against Mr.

Sacks under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331, 1337, and 2461(a).

5. Venue

in the Western District of Washington is proper under 28 U.S.C. § 1391(e),

as Mr. Sacks resides therein and no real property is involved in this action.

III.

operative facts

A. Background.

6. On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. In response, then-President George H.W. Bush declared a “national emergency” pursuant to Executive Order 12722. That “national emergency” remains in effect to the present day. Executive Order 19890 (July 31, 2003). In Executive Order 12722 and in Executive Order 12724 dated a week later, President Bush authorized the imposition of economic sanctions on Iraq.

7. Iraq’s invasion led to the First Gulf War. A coalition led by the United States defeated Iraq after an extensive bombing campaign.

8. Immediately after the conclusion of the First Gulf War, in March 1991, the United Nations reported on the extensive damage to Iraqi infrastructure caused by the U.S.-led bombing campaign. Then-Secretary-General Javier Perez de Cuellar dispatched a mission headed by Under-Secretary-General Martti Ahtisaari to assess the situation in Iraq. The Under-Secretary-General reported:

I and the members of my mission were fully conversant with media reports regarding the situation in Iraq and, of course, with the recent WHO/UNICEF report on water, sanitary, and health conditions in the Greater Baghdad area. It should, however, be said at once that nothing we had seen or read had quite prepared us for the particular form of devastation which has now befallen the country. The recent conflict has wrought near-apocalyptic results upon the economic infrastructure of what had been, until January 1991, a rather highly urbanized and mechanized society. Now, most means of modern life support have been destroyed or rendered tenuous. Iraq has, for some time to come, been relegated to a pre-industrial age, but with all the disabilities of post-industrial dependency on an intensive use of energy and technology.

The report recommended an immediate end to the embargo on imports of food and other essential supplies to prevent “imminent catastrophe.”

B. OFAC’s Regulations in Response to the “National Emergency.”

9. In January 1991, OFAC first promulgated regulations to enforce

economic sanctions against the people of Iraq.

Those regulations appear at 31

CFR Part 575.

10. OFAC purported to act under 50 U.S.C. §§ 1701(a) & 1702. These statutes grant the President certain powers to deal with an “unusual and extraordinary threat” posed by a “national emergency” declared by the President. Among those powers is the power to regulate certain financial transactions. These powers “may only be exercised to deal with an unusual and extraordinary threat with respect to which a national emergency has been declared . . . .” 50 U.S.C. § 1701(b).

11. OFAC’s regulations prohibit the importation of goods into Iraq. The regulations include “donated foodstuffs in humanitarian circumstances, and donated supplies intended strictly for medical purposes” unless those imports are “specifically licensed” by OFAC. 31 CFR § 575.205. OFAC’s regulations do not state the criteria by which OFAC grants such licenses. Nor do the regulations impose any deadline on OFAC to grant such licenses. Hence, OFAC has reserved to itself the unrestricted and unfettered power to keep food and medical supplies from reaching people in Iraq who need them.

12. OFAC has also prohibited travel to Iraq, including travel for

the purpose of bringing food and medical supplies to the Iraqi people. 31 CFR § 575.207 provides in relevant

part, and subject to very limited exceptions, that “no U.S. person may engage

in any transaction relating to travel by any U.S. citizen or permanent resident

alien to Iraq, or to activities by any U.S. citizen or permanent resident alien

within Iraq.” OFAC also prohibited “[a]ny transaction by a U.S. person relating to

transportation to or from Iraq.” 31 CFR

§ 575.208.

C. Enter Bert Sacks.

13. Bert Sacks has traveled to Iraq nine times. On each trip, Mr. Sacks has brought medicine and medical supplies and distributed them to civilians, many of them children, in civilian hospitals in Iraq. In 1997, he helped bring roughly $40,000 worth of medicine into Iraq for the purpose of relieving human suffering. Mr. Sacks also brought medicine and medical supplies to Iraq to publicize the effect of economic sanctions on the people of Iraq, especially children.

14. While in Iraq, Mr. Sacks has visited medical clinics and pediatric hospitals. He has seen the children who are dying there. Mr. Sacks has met with other U.S. citizens in Iraq to highlight the effects of U.S. policy there. Probably the best known among them is United States Representative Jim McDermott, who traveled to Iraq in 2002.

15. Mr. Sacks’ November 1997 trip to Iraq was covered in the national news media. In response to this particular trip, OFAC sought to punish Mr. Sacks. On December 3, 1998, OFAC sent a written “Prepenalty Notice” to Mr. Sacks and others. A true and correct copy of the Prepenalty Notice is attached hereto as Exhibit [1]. In the Prepenalty Notice, OFAC claimed Mr. Sacks had violated its regulations enforcing economic sanctions during his 1997 trip to Iraq. The Prepenalty Notice contained ten “counts,” only one of which, Count 6, was directed at Mr. Sacks. Count 6 made the following charge:

Between on or about [sic] November 21-30, 1997, Messrs. Handelman, Mullins, Sacks, and Zito, engaged in currency travel-related transactions to/from/within Iraq absent prior license or other authorization from OFAC. These currency transactions included, but are not limited to, the purchase of food, lodging, ground transportation, and incidentals.

OFAC proposed a penalty of $10,000 for Mr. Sacks “for Count 6” and invited written comments within thirty days.

16. On December 28, 1998, Mr. Sacks wrote back to OFAC:

I appreciate that you must see yourselves as doing your job to uphold US sanctions laws against Iraq, which I have violated. However I want to explain here, as I would to any personal friends of mine, why I have done this . . . .

You are correct to say in your prepenalty letter (12/3/98) that I brought “medical supplies and toys to Iraq” absent prior OFAC approval. We all recognize, I hope, that the $40,000 of medicines we brought to Iraq --- despite the lives it saved --- was essentially a symbolic act: it lasted the 22 million people of Iraq about 15 minutes, given their pre-sanctions needs of $1,000,000 of imported medicines per day. Further, we brought nothing towards the $10,000,000 of food imports Iraqis need per day. And we brought nothing towards the $22,000,000,000 of essential repairs for the life-supporting infrastructure needed to stop the water-borne epidemics in Iraq. These numbers long ago convinced me that the human crisis in Iraq cannot be solved by humanitarian aid --- but only by an end of economic sanctions.

The decision to turn to civil disobedience to end sanctions, in public defiance of the laws you are entrusted with enforcing, was not a natural one for me. I first spent two years of research, writing, and contacting people about the situation, but this failed to cast any significant public attention on the thousands of Iraqi children who were dying every month because of the bombed civilian infrastructure (unsafe drinking water) and sanctions (lack of food and medicines). In deciding to publicly violate sanctions, two events and two people played an important role for me.

The first is knowing that 150 years ago it was the highest law of the United States of America that runaway slaves from the South were legally “stolen property” of their owners. Anywhere in this country, an American was breaking the law to help such a slave escape via the “underground railroad.” The people I greatly admire from this terrible era in our history were not law-abiding citizens, but those who broke the law to help slaves. . . .

The second event influencing me is the deaths of millions of innocent civilians during WWII. I visited Auschwitz one year ago, just before my trip to Iraq. At both places over a million innocent civilians have died. I greatly admire the people who took personal risks to help Jews, against prevailing indifference and prejudice. . . .

These two events are certainly not

identical with events in Iraq, but the example of people motivated by high

moral considerations to “break the law” has given me encouragement to do the

same. . . .

17. After writing this letter, Mr. Sacks continued his work to

call attention to the effect of economic sanctions, and the regulations through

which OFAC seeks to enforce them, on the people of Iraq. Those sanctions have deprived many Iraqi

civilians, especially children, of the food, clean water, and medicine they

need to survive.

D. Economic Sanctions Contribute To the Deaths of Thousands of Young Children in Iraq Every Month.

18. Economic sanctions have prevented Iraq from rebuilding water treatment plants destroyed in the First Gulf War. Water treatment facilities were fairly widespread in Iraq until many were bombed during the First Gulf War, along with virtually all of the country’s electrical-generating plants that powered Iraq’s water and sewage treatment facilities. The resulting lack of potable water has led to the outbreak of severe diarrhea among young children, which is often fatal in the absence of medical treatment. OFAC regulations, however, have prevent people like Mr. Sacks from bringing medicine and medical supplies to Iraq. OFAC regulations also effectively prohibit the importation of the amount of food needed to feed the children of Iraq.

19. Each month, economic sanctions have helped cause the deaths of three to six thousand children in Iraq under five years of age. In 1992, the New England Journal of Medicine put the figure at 5,862 deaths per month for the first eight months of 1991 alone. (This does not include adults who have died in Iraq as a consequence of economic sanctions.)

20. In 2000, UNICEF issued a report entitled “UNICEF in Iraq.” The report warned: “Mounting evidence shows that the sanctions are having a devastating humanitarian impact on Iraq.” It quoted a 1997 report by the UN Human Rights Committee, which stated: “the effect of sanctions and blockades has been to cause suffering and death in Iraq, especially to children.”

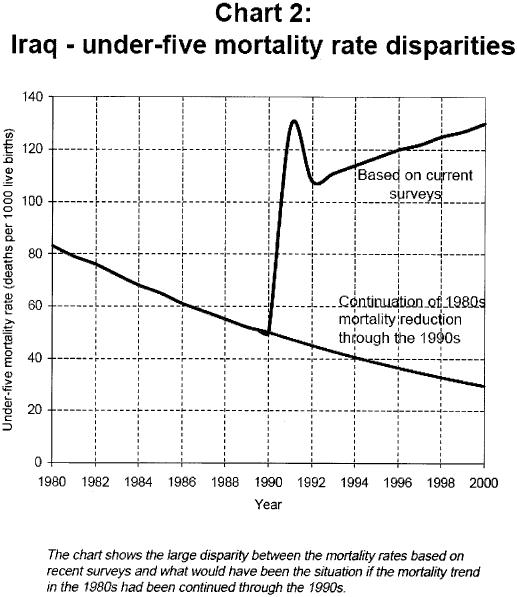

21. According to former

UNICEF Director Carol Bellamy, sanctions imposed by the United States through

the UN Security Council have reversed a decades-long decline in infant

mortality in Iraq. Ms. Bellamy cites

UNICEF reports that between 1991 and 1998, this reversal contributed to the

deaths of half a million children under the age of five. One such UNICEF report appears at http://www.unicef.org/reseval/pdfs/irqu5est.pdf.

It contains graphs such as the

following, which depict the upsurge in child mortality in Iraq after 1990, the

year economic sanctions were first imposed:

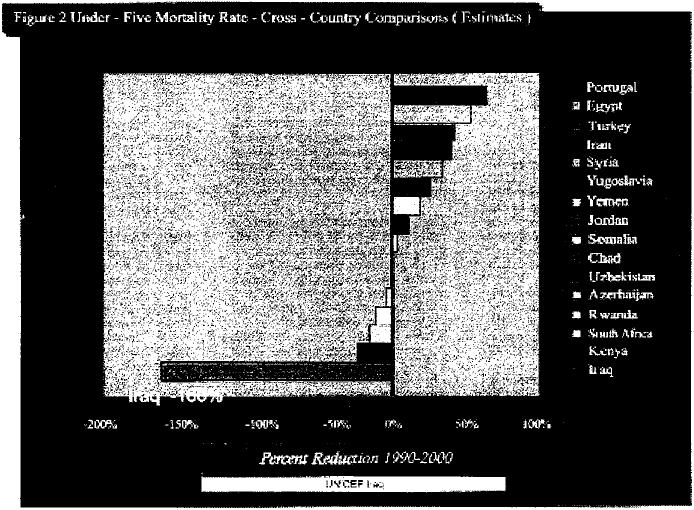

22. In

2003 UNICEF published another report, entitled “The Situation of Children in

Iraq.” See http://www.unicef.org/publications/pub_children_of_iraq_en.pdf. That

report states that a country like Iraq, which had an infant mortality rate of

40-60 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990, should have had a rate of 20-30 by

now. Id.

at 13. Instead, the infant mortality

rate in southern and central Iraq climbed to 107 deaths per 1,000 live births by

1999. Id. The under-five mortality

rate, meanwhile, rose from 56 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1985-89 to 131 in

1995-99. Id. The report contains the

following chart, which compares the 160% increase in childhood mortality in

Iraq to the (generally improving) trend in other countries:

Id. at 14. UNICEF attributes the increase in childhood mortality in Iraq to economic sanctions. Id. at 13.

23. In 1999, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer sent a team to Iraq to

report on conditions there. The

resulting articles, which are available on-line, document the deaths of Iraqi

children due to the absence of medical supplies. See http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/iraq/life1.shtml.

24. The situation has not improved since the end of the Second Gulf

War. UNICEF’s website (http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/iraq.html)

currently reports:

Even

before the most recent conflict began, many

children were highly vulnerable to disease and malnutrition. One in four

children aged under five is chronically malnourished. One in eight children die

before their fifth birthday.

25. Members of the United States government have publicly deemed

these widespread deaths of infants and children in Iraq to be “worth it.” In 1996 former Secretary of State (and then

U.S Ambassador to the UN) Madeleine Albright was asked: “We have heard that a

half million children have died. I mean, that's more children than died in

Hiroshima. And, you know, is the price worth it?” Ms. Albright responded, “I think this is a

very hard choice, but the price--we think the price is worth it.” Ms. Albright has later expressed regret for

this statement, but has insisted that sanctions are justified notwithstanding

the “starvation” and “horrors” experienced by the Iraqi people. She claimed sanctions did not preclude food

from reaching civilians in Iraq.

E.

Humanitarian Exemptions to Economic Sanctions

Have Not Stopped Children From Dying As a Result of Those Sanctions.

26. In theory, OFAC regulations allow food and medicine to be imported into Iraq. Food has also been brought into Iraq under the so-called “oil-for-food program,” which began in 1996. But widespread sanctions-related infant and child mortality remain.

27. As a result, the first two directors of the oil-for-food

program both resigned from the UN in protest.

The first director, Denis Halliday, served as United Nations Assistant

Secretary General and Humanitarian Coordinator in Iraq from September 1, 1997 until

the end of September 1998. He later explained:

Malnutrition is running at about 30 percent for children under 5 years

old. In terms of mortality, probably 5 or 6 thousand children are dying per

month. This is directly attributable to the impact of sanctions, which have

caused the breakdown of the clean water system, health facilities and all the

things that young children require. . . .

I do not want to administer a program that results in these kind of

figures.

A month after resigning, Mr. Halliday warned: “We are in the process of destroying an entire society. It is as simple and terrifying as that.”

28. Mr. Halliday was succeeded by Hans von Sponeck, who served as UN

Assistant Secretary General and Humanitarian Coordinator for Iraq. Mr. Von Sponeck served until February 2000,

when he, too, resigned. Mr. von Sponeck

stated, “I increasingly became aware that I was associated with a policy of

implementing an oil-for-food program that could not possibly meet the needs of

the Iraqi people.” He, too, cautioned,

“If we continue this policy when we fully recognize its consequences, we move

toward genocide.”

29. UNICEF reports confirm that the oil-for-food program “stopped the humanitarian situation from deteriorating, but did not greatly improve conditions for most Iraqis. This is partly because revenue has not been sufficient to comprehensively rehabilitate the country’s infrastructure.” This assessment is confirmed by recent events. In 1996, the oil-for-food program was set up to allow $2 billion of oil to be exported every 180 days. Yet L. Paul Bremer, currently the U.S. civilian administrator for Iraq, has publicly estimated that rebuilding Iraq will cost $100 billion. The oil-for-food program never made capital of this kind available to the people of Iraq.

UNICEF’s 2003 report, cited above, concludes:

[S]ince the introduction of the Oil for Food Programme, the nutritional status of children has not improved. One in five children in the south and centre of Iraq remain so malnourished that they need special feeding, and child sickness rates continue to be alarmingly high.

See

UNICEF, The

Situation of Children in Iraq (2003) at 11.

F. International Law Does Not Allow States To Deprive Civilians, Especially Mothers, Infants, and Young Children, of Food, Medicine, and Other Necessities.

30. International law is the supreme law of the land under the United States Constitution. Accordingly, to the extent OFAC regulations are inconsistent with international law, they are unconstitutional.

31. International custom and general principles of law recognized by civilized nations do not allow states to deprive civilians, especially mothers, infants, and children under the age of fifteen, of food, medicine, and other necessities of life.

32. Several treaties signed by the United States reflect or embody these principles of international law. Perhaps the best known of these is the Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Article 23 of the Geneva Convention states that even in war, parties to the treaty:

shall allow the free passage of all consignments of medical and hospital stores and objects necessary for religious worship intended only for civilians of another High Contracting Party, even if the latter is its adversary. It shall likewise permit the free passage of all consignments of essential foodstuffs, clothing and tonics intended for children under fifteen, expectant mothers and maternity cases.

The Geneva Convention codifies international custom and general principles of law recognized by civilized nations and applies those principles of law to the exigencies of wartime. Civilized nations recognize that depriving civilians, especially mothers and children, of the necessities of life is illegal and immoral, even (but not especially) during war.

33. Other treaties to which the United States is a party also codify or reflect these general principles of international law. One is the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Article II of the Convention defines genocide to include killing or causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of a group as well as deliberately inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about the partial or total physical destruction of the group. Legal scholars have suggested that economic sanctions against Iraq may have risen to the level of genocide within the meaning of the Convention.

34. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948, likewise springs from principles of international law that condemn state deprivation of food, medicine, and other necessities. Article 25(1) of the Universal Declaration states that

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services . . . .

Article 25(2) provides that “[m]otherhood and childhood are entitled to

special care and assistance.” Civilized

nations thus recognize that depriving people – particularly mothers, infants,

and young children – of “food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary

social services” constitutes a deprivation of their human rights.

35. Another

treaty, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, also springs from

these principles and affirms that states

may not deprive children of their means of subsistence. Article 24 of the Convention on the

Rights of the Child, for example, “recognize[s] the right of the child to the

enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health and to facilities for the

treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health.” The Convention states that nations “shall

strive to ensure that no child is deprived of his or her right of access to

such health care services.” Accordingly,

the Convention requires countries to “take appropriate measures: (a) To

diminish infant and child mortality; (b) To ensure the provision of necessary

medical assistance and health care to all children with emphasis on the

development of primary health care; (c) To combat disease and malnutrition,

including within the framework of primary health care, through, inter alia, the

application of readily available technology and through the provision of

adequate nutritious foods and clean drinking-water, taking into consideration

the dangers and risks of environmental pollution; [and] (d) To ensure

appropriate pre-natal and post-natal health care for mothers.”

36. OFAC regulations, and the economic sanctions they enforce, violate international law and the Constitution because they deny civilians, particular mothers and young children, of food, medicine, and other necessities of life. OFAC, therefore, may not constitutionally prevent individuals like Mr. Sacks from bringing food or medical supplies to civilians in Iraq.

37. Congress has implicitly recognized that international law does not allow states to deprive civilians, especially mothers and children, of food, medicine, and other necessities. Accordingly, Congress imposed several limits on OFAC’s power to impose economic sanctions.

38. 50 U.S.C. § 1702(b)(2), for example, provides that the “authority granted to the President by this section does not include the authority to regulate or prohibit, directly or indirectly . . . donations, by persons subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, of articles, such as food, clothing, and medicine, intended to be used to relieve human suffering.” The only exceptions are for donations that: (1) would “seriously impair” the President’s “ability to deal with any national emergency”; (2) are in response to “coercion against the proposed recipient or donor”; or (3) would endanger U.S. armed forces that “are engaged in hostilities or are in a situation where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances.

39. 50 U.S.C. § 1702(b)(4) provides: “The authority granted to the President by this section does not include the authority to regulate or prohibit, directly or indirectly . . . any transactions ordinarily incident to travel to or from any country, including importation of accompanied baggage for personal use, maintenance within any country including payment of living expenses and acquisition of goods or services for personal use, and arrangement or facilitation of such travel including nonscheduled air, sea, or land voyages.”

40. OFAC’s regulations exceed the authority Congress granted it.

G.

OFAC Enforces Its Sanctions Regulations to Quash

Conscientious Objectors.

41. Notwithstanding restrictions on OFAC’s power imposed by international law, by the Constitution, and by Congress, OFAC has persisted in its efforts to punish Mr. Sacks and others who bring food and medicine to civilians in Iraq. Nearly four years after Mr. Sacks responded to OFAC’s “Prepenalty Notice” in 1998, OFAC sent a written “Penalty Notice” to Mr. Sacks. A true and correct copy of the Penalty Notice, which is dated May 17, 2002, is attached hereto as Exhibit [2]. In it, OFAC informed Mr. Sacks:

You admitted the [initial Prepenalty] Notice’s allegation in Count 6 that you exported goods to Iraq absent prior OFAC approval and also stated that you decided to violate the U.S.-Government’s economic sanctions against Iraq as an act of civil disobedience. OFAC notes that you have admitted to Count 6 alleged in the Notice. The allegations included your currency travel-related transaction to/from/within Iraq absent prior license or other authorization from OFAC. . . . Accordingly, OFAC finds that you have violated the Regulations as alleged in Count 6 of the Notice.

The Penalty Notice concluded that a $10,000 penalty was appropriate.

42. Mr. Sacks responded to the notice and noted (correctly) that he had not admitted the charges set forth in Count 6; he had only admitted to bringing medicine to Iraq. As Mr. Sacks explained:

Count 6 [in your letter to us of December 3, 1998] deals only with “travel-related transactions … the purchase of food, lodging, ground transportation and incidentals.” I have never admitted to, nor supplied information about, any such transactions.

43. OFAC regulations theoretically allow a license to be granted to bring medicine to Iraq. But the regulations do not say how, when, or under what circumstances, OFAC will grant such a license. OFAC has accepted no restrictions on its power to deny such licenses.

44. In late 2002, Mr. Sacks sent a written request to OFAC under the Freedom of Information Act to assess OFAC’s willingness to grant licenses to U.S. citizens to travel to Iraq with medical supplies. In his request, Mr. Sacks asked OFAC to provide, among other things:

1. All internal or external summaries of requests to the Office of Foreign Assets Control since January 1991 by any individual, organization or business for license to travel to Iraq for the purpose of supplying medicine, health supplies, foodstuffs, and materials and supplies for essential civilian needs of the Iraqi population, including but not limited to summaries that show the final determination or status of those requests.

2. All requests to the Office of Foreign Assets Control since January 1991 by any individual, organization or business for license to travel to Iraq for the purpose of supplying medicine, health supplies, foodstuffs, and materials and supplies for essential civilian needs of the Iraqi population.

3. All requests to the Office of Foreign Assets Control since January 1991 by any individual, organization or business for license to export to Iraq medicine, health supplies, foodstuffs, and materials and supplies for essential civilian needs of the Iraqi population.

4. All responses by the Office of Foreign Assets Control to those requests numbered 2 and 3 above, including but not limited to a denial or granting of a license, or a request for further information.

Mr. Sacks has sent two follow-up letters seeking a response to his request. To date, OFAC has not responded to this request, which has been pending for nearly a year.

45. OFAC has targeted other alleged violators of its ban on travel and importation of medical supplies to Iraq. Several people who traveled to Iraq with medical supplies have also received civil penalty notices (including the other individuals named in the Prepenalty Notice to Mr. Sacks). So did Voices in the Wilderness, an organization that, like Mr. Sacks, seeks to publicize the effects of U.S. economic sanctions and bring an end to their use.

46. In June 2003, OFAC sued Voices in the Wilderness to recover a civil penalty. Voices in the Wilderness consists of many individuals who oppose economic sanctions in Iraq. Several of these individuals have, like Mr. Sacks, brought medicine and medical supplies to Iraq.

47. Then, in early August, 2003, an organization called Ocwen Federal Bank called Mr. Sacks to advise that it was attempting to collect the civil penalty on behalf of the federal government. Mr. Sacks subsequently received an August 11, 2003 letter from Ocwen Federal Bank, a true and correct copy of which is attached hereto as Exhibit [3]. That letter advised that Ocwen was attempting to collect Mr. Sacks’ alleged “debt” to OFAC for the civil penalty.

48. OFAC clearly intends to sue to collect the civil penalty it claims Mr. Sacks owes. Consequently, a case of actual controversy now exists concerning Mr. Sacks’ alleged obligation to pay such a penalty. Moreover, because Mr. Sacks has traveled to Iraq since the 1997 trip for which he was fined, a case of actual controversy exists as to OFAC’s authority to impose further penalties for these other trips.

49. Notwithstanding the fact that Mr. Sacks is the plaintiff in this cause, Mr. Sacks does not waive his right to have OFAC carry its burden of proving its entitlement to collect a civil penalty or any other matter on which OFAC has the burden of proof.

IV.

causes of action

50. OFAC’s attempts to collect a civil penalty are unlawful and unauthorized.

51. OFAC’s Prepenalty and Penalty Notices state that OFAC is seeking to collect an civil penalty from Mr. Sacks for “currency transactions,” namely “the purchase of food, lodging, ground transportation, and incidentals.” Yet OFAC lacks the statutory authority to do so. 50 U.S.C. § 1702(b)(4) expressly denies OFAC “the authority to regulate or prohibit, directly or indirectly . . . any transactions ordinarily incident to travel to or from any country, including importation of accompanied baggage for personal use, maintenance within any country including payment of living expenses and acquisition of goods or services for personal use, and arrangement or facilitation of such travel including nonscheduled air, sea, or land voyages.”

52. To the extent OFAC seeks to impose a penalty for the importation of medicine or medical supplies to Iraq, OFAC lacks the statutory authority to do so. 50 U.S.C. § 1702(b)(2) expressly denies OFAC the authority to regulate or prohibit, directly or indirectly . . . (2) donations, by persons subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, of articles, such as food, clothing, and medicine, intended to be used to relieve human suffering.” OFAC’s demand that Mr. Sacks obtain a license to donate medicine constitutes a prohibited attempt to directly or indirectly regulate (if not outright prohibit) those donations.

53. To the extent OFAC seeks to impose a penalty for the importation of medicine or medical supplies to Iraq, OFAC lacks the constitutional authority to do so. Government efforts to withhold food and needed medical supplies from innocent civilians, particularly mothers, infants, and young children, violate international law. This international law, to which the United States has acceded, is the supreme law of the land under the Supremacy Clause set forth in Article VI of the United States Constitution (“all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land”). OFAC may not punish Mr. Sacks in violation of international law and the Constitution of the United States.

54. According to OFAC’s Prepenalty Notice, its claim for a civil penalty arises from conduct by Mr. Sacks that took place “on or about November 21-30, 1997.” To the extent OFAC seeks a civil penalty for such conduct, it is untimely and is barred by the five-year statute of limitations that applies to the collection civil fines and penalties. 28 U.S.C. § 2461 provides:

Except as otherwise provided by Act

of Congress, an action, suit or proceeding for the enforcement of any civil

fine, penalty, or forfeiture, pecuniary or otherwise, shall not be entertained

unless commenced within five years from the date when the claim first accrued.

By its own admission, OFAC’s claim for a civil penalty first accrued over five years ago.

V.

relief requested

WHEREFORE Bert Sacks requests the following relief:

1. A declaration that OFAC is not entitled to collect a civil penalty from him for all of the following reasons:

a. OFAC lacks the statutory authority to regulate Mr. Sacks or others who seek to donate food and medicine to civilians in Iraq, and OFAC lacks the authority to prohibit Mr. Sacks or others from doing so;

b. OFAC lacks the statutory authority to regulate Mr. Sacks or others who seek to travel to Iraq for the purpose of donating food and medicine to civilians in Iraq, and OFAC lacks the authority to prohibit Mr. Sacks or others from doing so;

c. OFAC lacks the constitutional authority to prohibit Mr. Sacks or others from bringing food and medical supplies to Iraqi civilians, as international law to which the United States has acceded forbids the United States government from killing civilians, especially mothers, infants, and young children; and

d. OFAC’s claims, to the extent they arise from conduct that took place five or more years ago, are untimely and barred by the statute of limitations.

2. An order enjoining OFAC from further efforts to collect civil penalties from individuals who seek to travel to Iraq or donate food or medicine to civilians there; and

3. Such other and further relief as this Court deems just and proper.

DATED this 14th day of January, 2004.

GARVEY SCHUBERT BARER

By

Donald B. Scaramastra, WSBA #21416

Gary D. Swearingen, WSBA #24483

Attorneys for Plaintiff Bertram Sacks